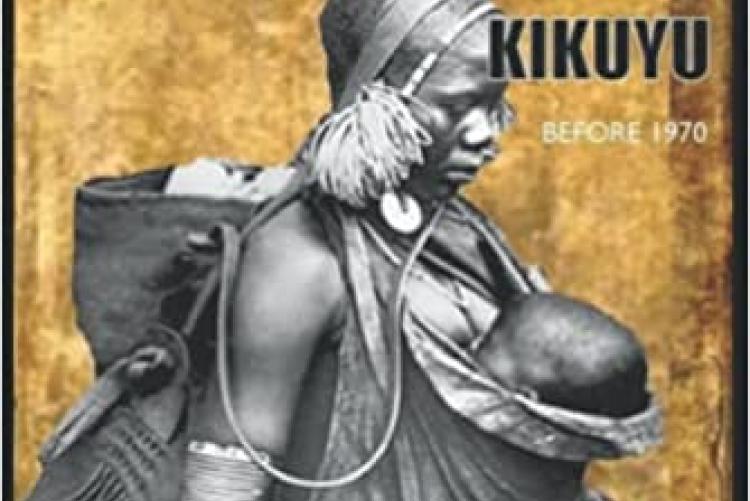

Dr.Samuel Mwĩtũria Maina will launch his book on "A Prehistoric People the Central Kikuyu Before 1970" at the French Cultural Centre on Saturday, 13th February 2022 from 2 pm-5 pm. Register to attend: https://forms.gle/3KUtJa1uncx7GGzt7

Dr. Maina is a senior lecturer of industrial design at the Department of Art and Design, Faculty of Built Environment and Design - The University of Nairobi, Kenya.

PREFACE

The book “A Prehistoric People THE CENTRAL KIKUYU Before 1970” expounds on the Central Gĩkũyũ who occupy Mũrang’a County, which is in the central part of Kenya. At various times in history, the Central Gĩkũyũ territory has been known as Ithanga, Mũkũrwe-inĩ, Gĩkuyu, Kĩrĩnyaga, Metumi, Fort Hall and finally Mũrang’a. They are the original Gĩkũyũ and direct descendants of Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi. The country of the Central Gĩkũyũ,' whose system of tribal organisation will be described in this book, lies between the southern Gĩkũyũ of Kĩambu (Kabete) and the northern Gĩkũyũ of nyĩrĩ (Gaki) all three lying in the central part of Kenya. Murang’a is divided into six administrative sub-counties: Kandara, Gatanga, Kĩharũ, kangĩma, Kĩgumo and Maragwa. The population, according to the 2019 census is (1,056,640) one million, fifty-six hundred, six hundred and forty. The Central Gĩkũyũ people are agriculturists, today keeping a few flocks of sheep and goats and cattle. They are also ardent businessmen.

The cultural and historical traditions of the Central Gĩkũyũ people have been verbally handed down from generation to generation. These traditions are quite distinct from the other two of the north and south. In writing this book, I sought to bring out this distinction to establish the difference with the southern Gĩkũyũ as was aptly captured by Louis Leakey in his treatise titled “southern kikuyu before 1903”. Probably the only and most comprehensive book on Gĩkũyũ culture, Leakey candidly dwelt on the southern Kikuyu and confesses to not having had much contact with what he wrongly summed up as northern kikuyu.

In that said north, there exists two distinct kikuyu cultural groupings that have never been studied to establish this glaring distinction between the Nyĩrĩ and Mũrang’a groupings.

From inception, the Central Gĩkũyũ carried forth their information and history through memory. In the book “a prehistoric people: the Central Gĩkũyũ before 1970”, effort was made to collect relevant information from sometimes very meagre sources to try to correct the misconception that the kikuyu are a homogenous people practicing a common culture. As a Central Gĩkũyũ myself, having been born and grown up there, it is clear after interaction with the other two, that the original Gĩkũyũ still exists in Mũrang’a (fig 15) as close to as it was during Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi era. It is from these original Gĩkũyũ that the other two, the southern and northern, developed after dispersal from Mũrang’a.

My objective was not to enter into controversy with those who have endeavoured, or are attempting, to describe the same things from outside observation. Instead, I sought to let the truth speak for itself. I also hoped that the reader will utilize the contents to solve real social problems by using the described efficacious methods and ideas.

I am a mũthuri wa kĩama (elder) of the second grade (Kĩama kia mbũri igĩrĩ) having fulfilled all the requirements of the same group. While the kĩama ‘died’ in the advent of colonialism and subsequent quasi-colonial African governments in Kĩambu and Nyĩrĩ, the kĩama in Mũrang’a never ceased its processes and functions. It has therefore been continuous since the first mwaki was established in Gĩkũyũ country. From my interaction with this mĩaki, I have for example come to establish why Leakey refused to publish an abridged copy of his thesis. Leakey must have been in a big dilemma. Having joined solemnly the Gĩkũyũ kĩama, Leaky was bound by his oath which I also went through and which I cannot explain here. His family may not have understood why he couldn’t publish despite the promise of incessant income and wealth.

In the course of research for this book, I came across the same dilemma despite, being a scholar, in fact a university lecturer at the University of Nairobi, as Leakey did, that I could not divulge all that I know due to the same oath Leakey took. From this you can imagine that I was not able in this book to write all and everything or detail that I know and found due to this predicament.

However, I made every effort to describe the daily activities and life of the Central Gĩkũyũ people from inception at mũkũrwe wa nyagathanga including, harvesting, care of animals, farming, trading, marriage, tribal raiding, song and dancing, law and law giving, customs related to sex, clothing and food, religion, death and disposal of the dead up to the colonial invasion, Mau Mau war and the aftermath up to 1970.

In this endeavour, I found out that within the Central Gĩkũyũ, everyone was provided for. Rules and regulations governed every aspect of life. Those rules had to be obeyed without question. Good among the people are those who kept the rules. The bad ones brought to themselves and family bad omen and uncleanliness, thus requiring debilitating amounts of expenses both human and material for cleansing ceremonies.

The Central Gĩkũyũ did not lack anything. Their land is fertile. Their security is guaranteed by the four holy mountains, kianjahi, kĩambirũirũ, Kĩrĩnyaga and nyandarũa. They had a system of government that covered every aspect of life. Before the coming of the colonialist, they lived in a kind of ‘garden of Eden’ which literally flowed with milk and honey, honey provided by their mwanĩki and milk by mũrĩithi.

In their territory, before the corrupt and evil colonial enterprise, the Central Gĩkũyũ had devised ways to solve all their social problems.

- Log in to post comments